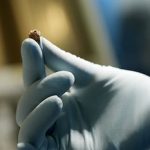

In the late 1970s, a team of archaeologists became obsessed with a set of mummies so unique that some thought it was a scam. They were located in the Tarim Basin, in northeastern China. Hundreds of naturally mummified human remains have rested there for centuries thanks to the arid and cold climate of the desert. As research progressed, scientists asked more questions regarding the origin and customs of the so-called “Tarim mummies.” But there was one particular doubt that raised the eyebrows of Qiaomei Fu’s team, paleogeneticist and director of the ancient DNA laboratory at the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. Some of the mummies had a mysterious white substance spread across their necks, and no one could explain what it was or why it was there. Twenty years later, thanks to the advancement of ancient DNA analysis techniques, the scientist has found the answer: kefir cheese.

Qiaomei and his team have managed, for the first time, to extract and analyze the genetic material preserved in samples of that cheese, which date back 3,600 years, making them the oldest ever recorded. The results of the research, published today Wednesday in the journal cellsuggest a new origin for this fermented food and provide evidence about how evolution and collaboration between humans and probiotic bacteria has always been very close. The author explains that foods like cheese are extremely difficult to preserve for thousands of years, which is why it is “a unique and valuable opportunity.” Analysis of this food can help scientists better understand prehistoric diet and culture.

“The interaction between people and microbes has always been with us. “Humans of the past used their wisdom to apply and domesticate microbes to preserve and produce fermented foods, which shaped specific lifestyles and promoted techno-cultural exchanges,” Qiaomei explains about his research. Using advanced ancient DNA recovery techniques, the researchers managed to reconstruct the genome of bacteria involved in fermentation processes and explored how humans had a direct influence on the evolution of these microorganisms.

It was a matter of survival. Developing food fermentation techniques in the Bronze Age made them more durable. In the case of dairy products, residents could convert raw milk into products such as kefir cheese, which not only lengthened their shelf life, but also made them more digestible, especially in genetically lactose intolerant populations.

The kefir route

Not long ago, kefir was thought to have originated in the mountainous region of the Caucasus and then spread to the rest of Europe and Asia. In fact, the etymological origin of the word is Turkish and means “blessing.” However, the study published in cell suggests other dispersal routes for this technique, raising the question of whether it actually originated independently in other parts of the world before spreading.

The key seems to be in the type of bacteria that were found in the samples. The researchers managed to extract DNA of the strain from the cheese Lactobacillusthe main microbe in the fermentation of kefir, whose origins are in Tibet. This showed a subtle difference, as the strains found in the mummy samples belonged to the subspecies kefiranofacienswhile strains located in Europe and other eastern coastal regions belong to the subspecies kefirgranum. Both are commonly found in today’s kefir grains. This reinforces the idea of multiple routes of cultural and food propagation. Although not only that.

During that long journey, the microbes did not stay still. The study helped determine how the Lactobacillus kefiranofaciens exchanged genetic material with related strains and improved, over time, their genetic stability and milk fermentation capabilities. Compared with the old Lactobacillusmodern bacteria are less likely to trigger an immune response and be rejected by the human intestine. This suggests that genetic exchanges also helped the Lactobacillus to better adapt to human hosts over thousands of years of interaction. That is to say, at the same time that humans adapted to bacteria in order to stay fed, bacteria, on an invisible scale, also adapted to humans in order to survive within them.

“People in the past already applied microbes to preserve and produce fermented foods from early on, and these production techniques spread among populations very widely,” says Qiaomei. And he adds: “Our new perspectives on microbial genomes are valuable, as they allow us to explore more details about changes in human lifestyle, cultural exchanges and, especially, interactions with the environment on an evolutionary scale.”

Thanks to this discovery, scientists will be able to better understand the co-evolution between humans and microbes over more than three thousand years. These symbiotic relationships, often ignored, although they continue to be perpetuated, helped humans adapt to new environmental conditions and improve their diet. The scientific – and the general public – fascination with the longest-lived samples is not an academic whim. It is explained, Qiaomei believes, because “perhaps, through the oldest things, people feel closer to their origins.”